A traditional Quinault ocean canoe carved from a single western red cedar tree. Photo by Rocco Saracina.

I had the opportunity to attend the 42nd Annual National Indian Timber Symposium earlier this month. The InterTribal Timber Council coordinates the event, which is hosted by a different tribe each year. This year we were welcomed onto the lands of the Quinault Indian Nation along the northern shores of Washington State. The council is a nation-wide consortium of Indian Tribes, Alaska Native Corporations, and individuals dedicated to improving the management of natural resources of importance to Native American communities.

The symposium’s theme, “Forests: Our Heritage from the Past, Our Legacy to the Future,” was brought to life for me during a full-day tour of the Quinault Indian Nation’s lands. We emerged from the forest and visited the Point Haynisisoos Cultural Site, which is the landing point of an annual canoe journey that brings together communities from across the Pacific Northwest. These traditional ocean-going canoes are a proud symbol of the lasting connection Indigenous people have with each other and their forests.

The Quinault explained this tradition may have been lost, if not for being revitalized by tribal elder Emmett Oliver in 1989. The canoe journey and celebration has grown over time. The most recent gathering hosted more than 10,000 people over a six-day spiritual celebration which shared traditional wisdom passed down through generations.

The experience reminded me of a conversation I had with SFI’s newest Board Member, Lennard Joe, President of the Nicola Tribal Association. The association is the advisory body for seven First Nations bands in British Columbia.

The Point Haynisisoos Cultural Site along the stormy western edge of the Quinault Tribal Forest. Photo by Rocco Saracina.

Len, as friends know him, explained that Indigenous people understand that forest productivity and markets are essential to economic prosperity. However, economics alone can’t support traditional ways of life.

That’s why, as Len puts it, forests must be managed to support “Cultural Survival Areas.” This concept bridges traditional ecological knowledge with modern forestry and predictive modeling to ensure forest practices preserve an abundance of cultural resources that Indigenous people rely on.

Cultural survival may sound drastic, though upon reflection it seems appropriate. For the Quinault, losing their tradition of ocean canoes for transportation, fishing, and ceremonies would have meant the death of an integral aspect of their culture. For many of us, this may be difficult to fully appreciate. Our cultures never faced forced removal from our lands, assimilation against our will, or the myriad other struggles that many Indigenous Peoples encountered in the past and still do today. In that context, Indigenous stewardship of forests is helping heal a grievous rift along a path towards beautiful cultural revival.

The largest known Sitka spruce tree in the world, nestled in the Quinault Tribal Forest. Photo by Rocco Saracina.

I don’t believe that “Cultural Survival Areas” is an official forestry term, but perhaps it should be. After all, forests are responsible for many aspects of both our culture and survival regardless of heritage. For professionals working in forestry, we know well that forests provide vital resources and services that everyone relies on, including the air we breathe, clean water that we drink, regulation of our climate, and much more. Forests can also provide a place of respite, and I would argue, a spiritual connection to something deep within us. A primordial part of who we are. That is why visiting the forest feels like going home, regardless of where you came from.

Though, perhaps the most poignant lesson I took from the National Indian Timber Symposium is a reflection on generosity and giving thanks. Throughout the week, nearly every speaker offered thanks to the Quinault, thanks to those in attendance, and thanks to the Creator. At meals, prayers were offered to respect the animals and plants harvested to feed us, and to the forests and lands, they came from.

Forests provide for our survival while asking nothing in return. They are so good at providing for us that most of us take their gifts for granted. With that in mind, next time you find yourself in the woods, take a moment to breathe in that fresh air and realize how blessed we are.

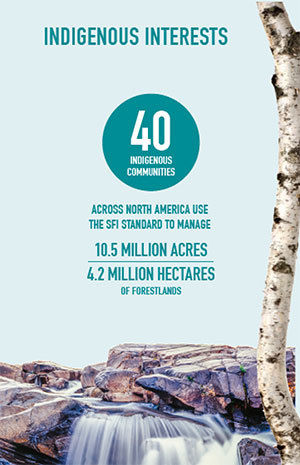

SFI Engages with Indigenous Communities

SFI grants have supported Indigenous communities and projects in the U.S. Southwest, Canada’s boreal forest, the U.S. Northeast and the Pacific Northwest.

In the spring of 2018, SFI Launched the SFI Small Scale Forest Management Module for Indigenous Peoples, Families and Communities to engage more Indigenous communities in sustainable forest management certification.

SFI, through Project Learning Tree Canada, is also thrilled to be placing Indigenous youth across Canada in Green Jobs funded in part by the Government of Canada.